Review

- Food

- Lab

- Cooking

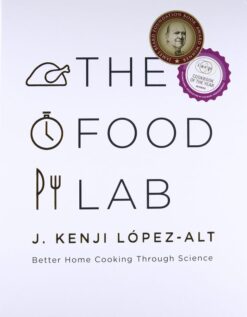

“For avid home cooks who came of age in the digital era, there may be few voices more authoritative than that of J. Kenji López-Alt, the nerd king of Internet cooking…He is reliable, personable and unpretentious. He is also a gifted explainer, making difficult concepts easy to grasp for those of us with a lifelong lack of aptitude for the sciences.” –The New York Times

“Lopez-Alt’s application of scientific rigour to home cooking is actually a lot of fun. Any book that devotes 13 pages to achieving the perfect chip is all right by us.”

–The 25 best food books of 2015, The Observer Food Monthly

“López-Alt shows that conventional methods do not always work well and explains how home cooks can achieve better results using new techniques. A bestseller in America.”

—The Irish Sunday Times

“…a must-read for home cooks…Buy this book for your favourite food nerd and you’ll get precious little conversation out of them on Christmas Day. It questions the techniques we use day-to-day, examining the science as well as providing recipes and a fair bit of humour. It’s peppered with useful facts, too…My Christmas cooking has changed forever.”

The Food Lab

—The Telegraph

“…take your time. You’ll learn a lot.”

The 10 best cookbooks of 2015, The Washington Post

“…it is the only book you need to become a seriously good cook.”

—Chemistry World

“He’s [J. Kenji López-Alt] got science on his side (and a degree from MIT) and has spent countless business hours thinking about and reverse-engineering what, exactly, makes delicious food work. (We highly recommend picking up his 1,000 page, James Beard award-winning cookbook…”

–GQ Magazine

“It will make you question just about everything you know about cooking as well as give you new ways of doing old things to make them better… a hefty tome that is well worth its price.”

–Foodepedia

{ What’s in this book? }

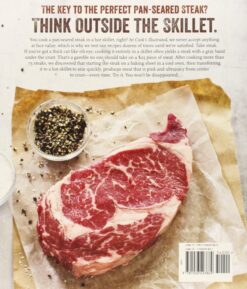

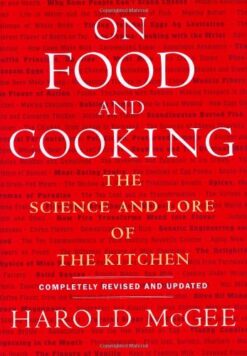

About twenty years ago, celebrated food scientist, author, and personal hero

Harold McGee made a simple statement: contrary to popular belief, searing meat

before roasting it does not “lock in the juices.†” Now, saying this to a cook was

like telling a physicist that rocks fall upward or an Italian that pizza was invented

in Iceland. Ever since the mid-nineteenth century, when German food scientist

Justus von Liebig had first put forth the theory that searing meat at very high

temperatures essentially cauterises its surface and creates a moistureproof

barrier, it had been accepted as culinary fact. And for the next century and a half,

this great discovery was embraced by world-famous chefs (including Auguste

Escoffier, the father of French cuisine) and passed on from mentor to apprentice

and from cookbook writer to home cook.

The Food Lab

You’d think that with all that working against him, McGee must have used the

world’s most powerful computer, or at the very least a scanning electron

microscope, to prove his assertion, right? Nope. His proof was as simple as

looking at a piece of meat. He noticed that when you sear a steak on one side,

then flip it over and cook it on the second side, juices from the interior of the

steak are squeezed out of the top—the very side that was supposedly now

impermeable to moisture loss!

It was an observation that anyone who’s ever cooked a steak could have made,

and one that has since led restaurants to completely revise their cooking

methods. Indeed, many high-end restaurants these days cook their steaks first,

sealed in plastic, in low-temperature water baths, searing them only at the end in

order to add flavor. The result is steaks that are juicier, moister, and more tender

than anything the world was eating before von Liebig’s erroneous assertion was

finally disproved.

The question is, if debunking von Liebig’s theory was such a simple task, why

did it take nearly a hundred and fifty years to do it? The answer lies in the fact

that cooking has always been considered a craft, not a science. Restaurant cooks

act as apprentices, learning, but not questioning, their chefs’ techniques. Home

cooks follow the notes and recipes of their mothers and grandmothers or

cookbooks—perhaps tweaking them here and there to suit modern tastes, but

never challenging the fundamentals.

It’s only in recent times that cooks have finally begun to break out of this

shell. Restaurants that revel in using the science of cookery to come up with new

techniques that result in pleasing and often surprising outcomes are not just

proliferating but are consistently ranked as the best in the world (Chicago’s

Alinea or Spain’s now-closed El Bulli, for example). It’s an indication that as a

population, we’re finally beginning to see cooking for what it truly is: a

scientific engineering problem in which the inputs are raw ingredients and

technique and the outputs are deliciously edible results.

Now, don’t get me wrong. I’m not out to try and prove to you that foams are

the way of the future or that your eggs need to be cooked in a steam-injected,

pressure-controlled oven to come out right. I’m not here to push some sort of

newfangled, fancified, plated-with-tweezers, deconstructed/reconstructed

cuisine. Quite the opposite, in fact.

My job is simple: to prove to you that even the simplest of foods—

hamburgers, mashed potatoes, roasted Brussels sprouts, chicken soup, even a

g&#amn salad—are every bit as fascinating, interesting, storied, and delicious as

what the chefs wearing the fanciest pants these days are concocting. I mean,

have you ever stopped to marvel about exactly what goes on inside a hamburger

when you cook it? The simultaneous complexity and simplicity of a patty

formed from the chopped muscle mass of selected parts of a remarkably intricate

animal, seasoned with salt and pepper, seared on a hot piece of metal, and then

slipped into a soft toasted bun? You haven’t? Well, let me give you a quick

rundown to show you what I’m talking about.

ON HAMBURGERS

Hamburgers start as patties of beef . . . , no, let me back up a bit. Burgers

actually start as ground beef that’s then formed into . . . , no, sorry, even further

back. Hamburgers start with whole cuts of beef that are then ground into . . .

Wait a minute, let’s get all Inception on this and go one level deeper: hamburgers

start with cows—animals that live exceedingly complicated lives, that can differ

not only in breed and feed, but also in terms of exercise, terrain they’re exposed

to, how and when they’re slaughtered, and whether they live on grass their

whole lives or are supplemented with grain. From these animals come many cuts

of meat that vary in flavor according to fat content, their function during the

animal’s life, and its specific diet. Blending specially selected cuts will lead to

ground beef with the optimal flavor and fat profile.

From there, it’s just a simple matter of grinding, forming patties, and cooking,

right?

The Food Lab

Not so fast. How you grind your beef can have a profound impact on the

texture of the finished burgers. Think all ground beef is created equal? Think

again. And what about salting? Do you salt the meat and blend it in, or do you

salt the outside of the patties? How do you form those patties? Pressing the beef

into a ball and flattening it works, but is that really the best way? And what

causes those burgers to puff up into softball-shaped spherical blobs when you

cook them anyway? Once you start opening your mind to the wonders of the

kitchen, once you start asking what’s really going on inside your food while you

cook it, you’ll find that the questions keep coming and coming, and that the

answers will become more and more fascinating.

Not only does answering questions about burgers help you to cook your

burgers better, but it also reveals applications to all sorts of other situations. We

start big fat burgers off on the cooler side of the grill and finish ’em with a sear

in order to get a nice, perfectly even medium-rare color throughout, along with a

strong, crusty sear. Guess what the best way to cook a big fat steak is? You got

it: the exact same method applies, because the proteins and fat in a steak are

similar to those in a hamburger.

Still not too sure what I mean? Don’t worry, we’ll answer all of these

questions and more in due time.

THE FIRST STEP TO WINNING IS LEARNING

HOW NOT TO FAIL

Have you ever made the same recipe a half dozen times with great results, only

to find that on the seventh time, it completely fails? The meat loaf comes out

tough, perhaps, or the pizza dough just doesn’t rise. Oftentimes it’s difficult to

point to exactly what went wrong. If you’re a tinkerer in the kitchen, you like to

modify recipes a bit here and there to suit your own taste or mood. That’s all

well and good, and luckily, the first six times, your modifications didn’t affect

the outcome of the recipe. What changed on that seventh time? Could it be the

extra salt you added? Perhaps the temperature of the room? Or maybe it’s that

you ran out of olive oil and used canola instead. Perhaps your stand mixer was

on the fritz, so you blended everything by hand.

The Food Lab

The point is, there are many ways you can stray from a written recipe, but

only some of those forays will cause the recipe to fail. Being able to identify

exactly which parts of a recipe are essential to the quality of the finished product

and which parts are just decoration is a practical skill that will open up your

opportunities in the kitchen as never before. Once you understand the basic

science of how and why a recipe works, you suddenly find that you’ve freed

yourself from the shackles of recipes. You can modify as you see fit, fully

confident that the outcome will be a success.

Take a recipe for Italian sausage, for instance. The recipe in this book has you

combine pork shoulder with salt and some aromatics, let the meat rest overnight,

and then grind it and knead it the next day. Now, you’ve tasted my Italian

sausage, and fair enough, you think it’s got too much fennel. OK, so you use less

fennel and more marjoram the next time instead. Because you’ve read the

sausage chapter and understand that the keys to a great-textured sausage are the

interaction between the salt and meat and the method by which the ground meat

is mixed, you’re confident that changing the spicing will still allow you to

produce a great-tasting link. At the same time, you know that salt is what

dissolves muscle proteins and allows them to cross-link, giving your sausage that

snappy, juicy texture, so you can’t cut back on the salt the same way you can

with the fennel. Likewise, you know that you can make your sausage out of

turkey or lamb if you’d like, but you can’t change the fat content if you want it

to remain juicy.

The Food Lab

Fact: Cooking by rote—even when your mentors are some of the greatest

chefs in the world—is paralysing. Only by understanding the underlying

principles involved in cookery can you free yourself from both recipes and

blindly accepted conventional wisdom.

Starting to get an idea of what I’m talking about? Freedom. That’s what.

WHY THIS BOOK?

In many ways, the blog format is ideal for the type of work I do. I get to write

about things in a pretty informal way and in return, my readers tell me what they

think, ask insightful questions, and let me know what they’d like to see me

tackle next. It’s communal, and I owe my success as a blogger as much to my

readers and my ever-supportive, always fun, incredible coworkers and fellow

bloggers as I do to myself.

That said, there are limits to what the blogging platform can support. It’s great

for short articles, it does pictures OK, but good charts? Good graphs? Good,

easy-to-understand layout? Long-form content? Forget about it. That’s where

this book comes in. It represents the culmination of not just a decade and a half

of cooking and studying the science of everyday foods, but of years of learning

how to apply this science in ways that can help home cooks cook everyday food

in better, tastier ways.

What you won’t find in this book are fancy-pants recipes calling for unfamiliar,

ingredients or difficult techniques or chemicals or even much special equipment

beyond, say, a food processor or a beer cooler. You also won’t find any desserts.

They just aren’t my thing, and rather than fake a few of ’em, I figured I’d just

own up to the fact that they just don’t interest me in the way savory food does.

(Remember that whole thing about not doing anything that I don’t love doing?)

What you will find here is a thorough examination of classic recipes. You’ll

find out why your fried chicken skin gets crisp, what’s going on inside a potato

as you mash it, how baking powder helps your pancakes rise. Not only that, but

you’ll discover that in many (most?) cases, the most traditional methods of

cooking are in fact not the ideal way to reach the desired end results—and you’ll

find plenty of recipes and instructions that tell you how to get better results. (Did

you know that you can parcook pasta in room-temperature tap water? Or that the

key to perfect French fries is vinegar?)

You’ll probably find that I talk about my wife and my dogs a bit too much,

and that I’m an confusing fan of both the Beatles and the pun, that lowest form of

wit. I may rightfully be accused of making abstruse references to any or all of

the following topics: The Simpsons. Cartoons and movies from the 1980s. Star

Wars. British comedians. The Big Lebowski. MacGyver. To these crimes, I plead

guilty, but I will not repent.

The Food Lab

Occasionally you will come across an experiment designed for you to carry

out yourself at home. All of these experiments are party-friendly, and most of

them are kid-friendly too, so make sure you’ve got company around if you’re

going to attempt them!

Some of you may use this book solely for the recipes, and there’s nothing

wrong with that. I’ll still like you. I’ve done my best to write them as clearly and

concisely as possible, and I guarantee each and every one of them will work as

advertised (provided you follow the instructions). If they don’t work for you, I

want to hear about it! Others may read through the entire book without ever

cooking a single thing from it.I might even like you guys more than I like the

recipe-only guys,for it’s what’s going on behind

the scenes, or under that well browned crust,

that really interests me. If you’re the armchair-cook type,

you’re in luck. This book was written to

work from front to back. Recipes in later chapters build on basic scientific

principles discussed in earlier chapters. On the other hand, if you like skipping

around—say, potato salad doesn’t interest you but roast beef sure does—well,

you won’t have much trouble either.

I’ve done my best to make each lesson self contained, cross-referencing earlier chapters when necessary.

The Food Lab

One thing I want to make clear here: This book is nowhere near

comprehensive. Why would I put myself down like that? Well, it’s because the

whole point of science is that it’s a never-ending quest for knowledge. No matter

how much we know about the world around us, the world inside a block of

cheese, or the world contained in an eggshell, the amount that we don’t know

will always be much greater than what we do. The moment we think we know

all the answers is the moment we stop learning, and I truly hope that time never

comes for me. In the words of Socrates Johnson: “All we know is that we know

nothing.”

If there are three rules that I think would make the world a better place if

everyone followed them, it’d be these: challenge everything all the time, taste

everything at least once, and relax, it’s only pizza.

SO WHY TRUST ME?

When I chime in on online message boards, when I write blog posts that make

some pretty bold claims (like, say, that frying in hotter oil actually makes food

absorb more grease, not less—see here), I often get the same questions shot back

at me: Says who? Why should I trust you? I’ve been cooking my food [X] way

since before you were born, who are you to say that there’s a better way?

Well, there are a number of answers I could give to this question: It’s my job

to study food, test it, and answer questions about it. I have a degree from one of

the top engineering schools in the country. I spent a good eight years cooking

behind the stoves of some of the best restaurants in the country. I’ve edited

recipes and articles in food magazines and on websites for almost a decade.

These are all pretty good reasons to put your faith in what I say, but the truth of

the matter is this: you shouldn’t trust me.

You see, “Just trust me” was the way of the old cooks.

The MO of the master apprentice relationship.

The Food Lab

Do what I say and do it now, because I say so. And that’s

exactly the mentality we’re trying to fight here. I want you to be sceptical.

Science is built on scepticism. Galileo didn’t come to the conclusion that the

Earth revolves around the sun, not the other way around, by blindly accepting

what everyone else was telling him. He challenged conventional wisdom, came

up with new hypotheses to describe the world around him, tested those

hypotheses, and then and only then did he ask people to believe in the madness

that he was spouting from behind that awesome beard of his. He did, of course,

die under house arrest after being tried by the Roman Inquisition for all of his

troubles. (Let’s hope that doesn’t happen to any of you budding kitchen

scientists.) And that was for something as trivial as describing the shape of the

solar system. Meanwhile, we’re here tackling the big issues. Pancakes and meat

loaf deserve at least as much scrutiny!

The point is this: if at any time while reading this book you come across

something I’ve written that just doesn’t seem right, something that seems as if it

hasn’t been sufficiently tested, something that isn’t rigorously explained, then I

fully expect you to call me out on it. Test it for yourself. Make your own

hypotheses and design your own experiments. Heck, just e-mail me and tell me

where you think I went wrong. I’ll appreciate it.

The Food Lab

Honestly.

The first rule of science is that while we can always get closer to the truth,

there is never a final answer. There are new discoveries made and experiments

performed every day that can turn conventional wisdom on its head. If five years

from now somebody hasn’t discovered that at least one fact in this book is

glaringly wrong, it means that people aren’t thinking critically enough.

But some of you might be wondering now, what exactly is science? It’s a

really good question, and a topic that’s often misunderstood. Let’s talk about it a

bit.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.